The COVID-19 pandemic has created ambiguity for some organizations over whether to stay the course on their regular pay equity assessments and resulting remediation actions. To date, all of the companies Mercer works with to promote equity are continuing their work; however, many organizations are questioning whether and how their focus on pay equity can hold up, as they face a new imperative to focus on operational issues and cost containment or reduction.

Pay Equity Is On the Rise

Six years after Mercer’s original When Women Thrive research report, the company released a significant 2020 update showing a sizable increase in the percentage of organizations conducting pay equity analysis: up from 35% to 56%.

The increase reflects what has been a growing commitment of corporate leaders to achieve pay equity, as well as continued pressure from governments and activist investors for proactive management of pay equity and disclosure of relevant statistics.

In fact, Arjuna Capital just released its third Gender Pay Scorecard, which grades companies for their achievement of equity and their transparency. It also cites pledges by many to complete annual reporting and related efforts concerning diversity and inclusion. The commitment by these companies to rigorous, global review performed on an annual basis — and embedded in the annual compensation process — represents important progress achieved on this issue, for the companies and for society.

The Value of Statistical Modeling

Rigorous pay equity assessments identify employees who appear to be underpaid as compared to “similarly situated” coworkers, based on estimation of statistical models of pay that account for the multiple factors that legitimately influence pay (not gender or race). These models produce predicted pay levels for each employee that companies can use as a benchmark for their actual pay.

Employees are considered underpaid if their actual pay is less than their predicted pay, beyond a range defined by statistically determined confidence intervals. All too often, those identified as underpaid — what we call “negative outliers” — are disproportionately female and/or not white.

So, remediation efforts that make pay adjustments for negative outliers can help organizations make progress on reducing overall gender and/or racial pay disparities. Organizations that do this work routinely budget for these pay adjustments beyond the annual merit increase.

Threat Posed by the Current Crisis

It is difficult to implement pay increases to correct for inequities when, for many, pay increases of any kind are off the table and furloughs or layoffs have either taken place or are under consideration.

So what should organizations do under these circumstances? The authors advise focusing on four areas of action:

Continue to assess the risks.

Progress earned over the years from significant investments to eliminate gaps and preclude such gaps from reemerging can be quickly lost if consistent monitoring of pay equity simply stops.

We know that the very process of pay equity evaluation itself can be a broad deterrent to discrimination. Mercer’s 2015 When Women Thrive research showed that those companies with rigorous, regular pay equity review processes were more likely to have equity across employment practices — in hiring, promotion and retention — leading to greater workforce diversity.

Lowering the review standard, even for a year, can lead managers to question the organization’s continued commitment and create longer-term, broader challenges. A resurgence of inequities could result.

Scale the response where budgets are limited.

Where disparities are identified, actions (generally, pay adjustments) should be considered; however, such actions can be phased in over time, with a short-term emphasis on maintenance of position over progress.

Robust pay equity processes are repeated annually, providing opportunity to accelerate further when budget dollars are again available.

Consider new opportunities to counter gaps.

In the current crisis, pay reductions will be a reality for many. Given that reality, why not push the pay reductions (in the form of salary or bonus cuts) to those who are already “overpaid”?

Mercer’s work over the years shows clearly that a focus on the overpaid, commonly a population with a high representation of men, can dramatically accelerate progress in closing overall pay gaps; indeed, it may be the only way to close them fully.

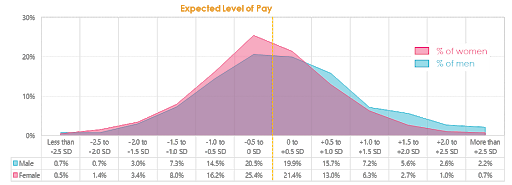

The exhibit below represents this case, blinded from a specific organization. The distributions of “residuals” — differences between actual and expected pay levels in terms of standard deviations — by gender, show that men are much more likely to be represented with high rates of excess pay.

Percentage of Women and Men in Different Brackets of Pay Relative to Expectation and the Greater Representation of Men Among Those “Overpaid”:

A further benefit of this approach is that there is no cash outlay associated with working from this end of the pay distribution. Policies that may have been inconceivable in normal times may suddenly be realistic and reasonable, and they can be extremely effective.

A robust, statistically driven pay equity analysis will generally represent many cases to contain and reduce pay. These cases represent opportunities beyond the pay equity imperative to control costs broadly.

Assess and address root causes of pay inequity.

It is very likely that workforce actions taken by organizations in response to the pandemic will have direct effects on some of the factors that most influence pay. Of real concern is that they may play out differently for women and people of color than they do for men and white people.

For example, organizations that concentrate their furloughs or layoffs on more recently hired employees — relying on a “last in, first out” model — may unwittingly widen pay gaps for their incumbent women and people of color.

Many organizations have engaged in concerted efforts to hire more women and people of color. In the tight labor markets of recent years, such organizations have paid sizable pay premia for new hires just to get them in the door.

To the extent that women and people of color are overrepresented among new hires, removing them from the workforce would reduce the number of relatively higher-paid employees among this cohort and thereby aggravate gender and racial pay differences for remaining incumbents.

The efforts companies have taken of late to ensure women come in at equitable pay rates would further exacerbate this impact. This is but one illustration that speaks to a larger point: The results from pay equity modeling can inform decisions about a host of workforce practices that organizations are necessarily contemplating as they respond to the deteriorating business climate.

With a Crisis Comes Opportunity

Winston Churchill said, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” This crisis poses a stark and unprecedented challenge to almost all organizations. How effectively they respond will determine in large part who comes out with a competitive advantage or even who survives.

We know that companies with strong pay equity processes support cultures that provide access to high-performing, diverse talent. That access continues to matter when we have to “do more with less.”

Pay equity analysis can be an important part of the response to the crisis itself, providing an avenue to help ensure that new workforce risks are identified and mitigated and that organizations seize new opportunities to optimize their workforce investments for short- and long-term gain.